Four traps that kill team alignment and progress — and what to do

I was recently asked to run an upskilling session on managing teams and projects. I decided to focus on what to do when projects go off track. Our people really enjoyed the session, so this blog captures the ideas for others to share in the future.

__________This blog describes four traps that teams commonly fall into. Each trap exists somewhere on the continuum from setting plans to executing plans. At their core, each trap relates to decision-making.

The agreement trap: A lack of agreement on the work that is most important to achieving your goals.

The leader trap: A lack of clarity on who is making the decision, who needs to be involved, and who doesn’t.

The adaptation trap: Failing to update your strategy with new information about efficacy or context.

The pacing trap: Confusion or disagreement on when to move quickly and when to slow down.

1 The agreement trap

A lack of agreement on the work that is most important to achieving your goals.

The agreement trap has two appearances:

Team members passionately debate which items are low, medium, and high priority during goal setting, such as OKR planning

Team members start working on different items, pulling focus in different directions

The agreement trap can be hard to resolve for two reasons. Firstly, because team members genuinely have different perspectives on what’s most important. Or, secondly, because team members have similar perspectives, but talk past each other in an effort to be heard.

Most commonly, the challenge is not that you have competing — or even different — views. In fact, these disagreements could quickly resolve if only individual preferences were clear and specific. When individuals make their perspective clear and specific, you can readily compare logic and align on a point of view that takes into account each person’s preference.

What to do: Use a system to clarify which tasks each team member thinks are a high and low priority. Critically, the system must remove ambiguity from the conversation. I recommend a ‘voting’ system, where team members allocate numerical values to tasks. For example, allocate each team member 100 points to divy up between the tasks to be completed. They may allocate their points how ever they choose, but must explain their rationale at the end. Note this exercise assumes (fairly so) that team members have reasonable insight to the work.

There are multiple benefits of running the exercise:

Forcing people to allocate points (or any kind of numerical value) reveals preferences in a clearer and more precise way than words do (Jordan and Zeke probably both said Project A was “important” but only by using this system can we see what “important” means to each of them)

Rather than talking past each other, team members now have ‘data’ to have a more robust and helpful conversation

You can quickly see which projects rise to the top (and bottom) of the priority list

2 The leader trap

A lack of clarity on who is making the decision, who needs to be involved, and who doesn’t.

The leader trap occurs when you don’t explicitly and publicly define each person’s responsibilities. You assume you know who is doing what, but we hold different views. A telltale sign is when your team starts to stall and it’s not clear why. Chances are everyone is waiting for the ‘leader’ to step in — but who is it? This also relates to the diffusion of responsibility challenge. With a team of 5+, individuals expect someone else will pick up the work, which can leave important tasks neglected.

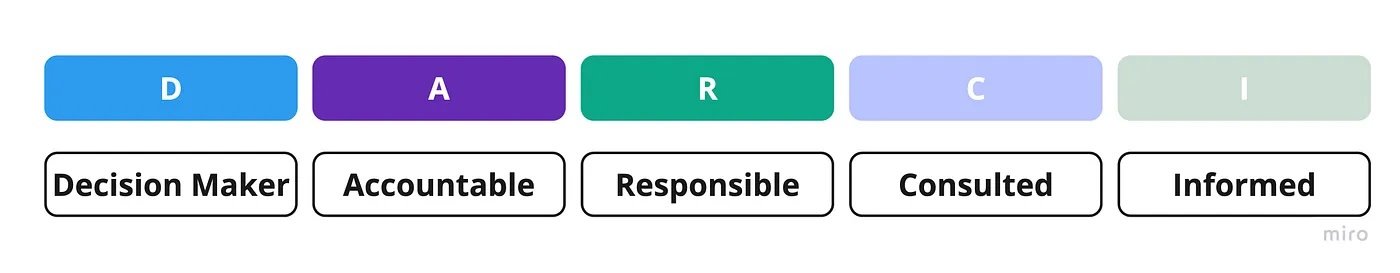

What to do: The DARCI framework, created by McKinsey, is a framework to identify the right individuals for each of the categories:

Guidance for using DARCI:

Decision-maker: this should be a very small list of people and only those who are responsible for the business outcome you’re chasing.

Accountable: this is the person charged with leading the project from start to end. There should only ever be one person named here. Ever!

Responsible: these are the team members responsible for carrying out the project.

Consulted: these are people whose buy-in you need and/or whose perspective is integral.

Informed: anyone who needs to be kept up to date with project progress, but doesn’t have a participatory role in the project.

3 The adaptation trap

Failing to update your strategy with new information about efficacy or context.

You’re at risk of the adaptation trap if your team has been in the weeds for days on end. This is more likely to occur when you feel an urgency to get the work done. This urgency becomes a distraction (or persuasion) to keep going and pause for nothing. As a result, we miss new data points, relevant feedback, and messages from the external world which would have signaled a better path forward. A good trick is to ask the last time someone on the team spoke with a beneficiary (or client).

What to do: Admittedly, this trap is not a straightforward problem to fix. Overcoming challenges or stagnation in strategy requires an iterative approach to strategy design and delivery. And, adopting an iterative approach is as much about your mindset as it is about your strategy and planning process.

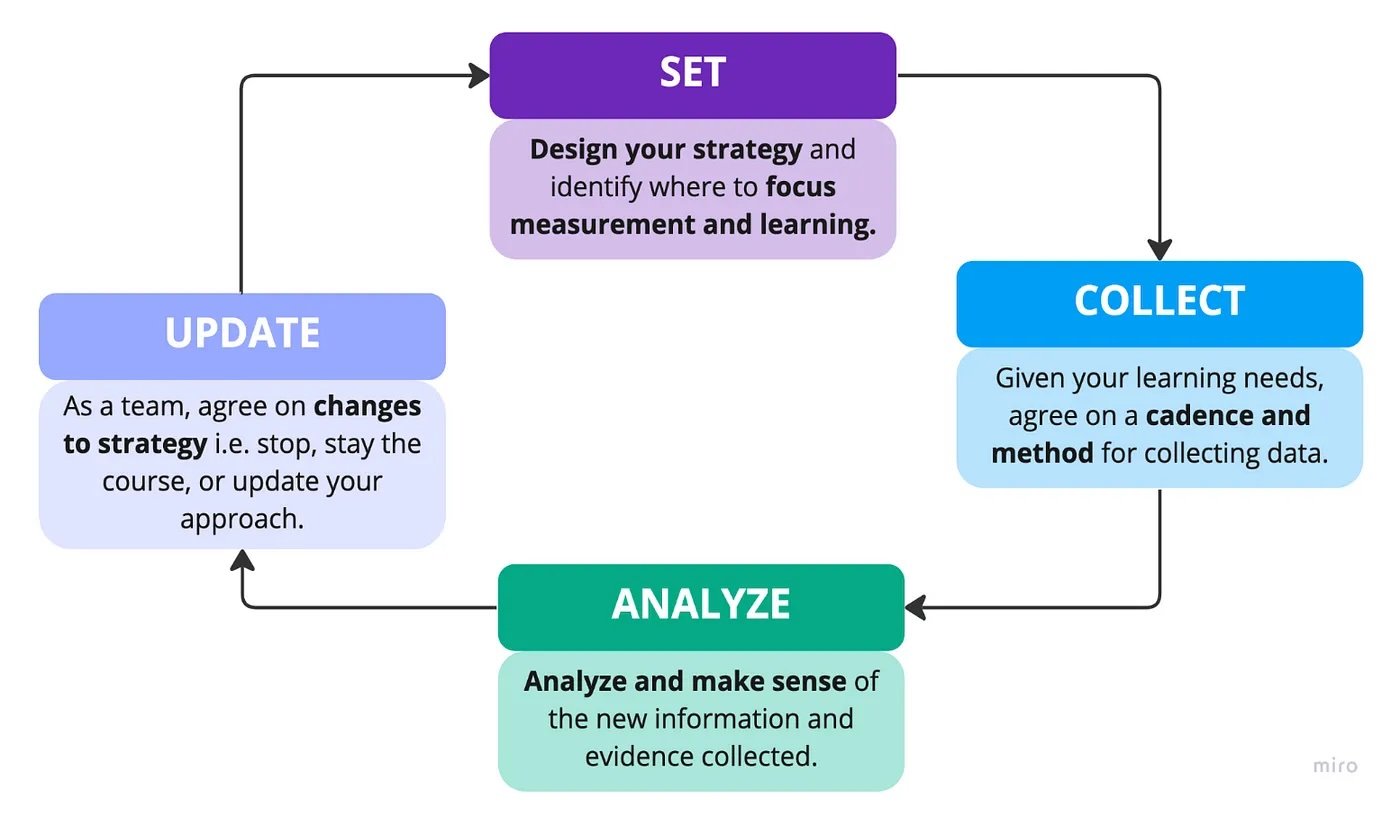

I created the framework below as a guide to ‘strategic iteration’. The framework centers measurement and learning in the strategy design/delivery process. It begins when you set your strategy. At this point, you must also identify the data/information you require to validate your approach and thus increase confidence that you’re using the winning strategy. From there, you can agree on an approach and cadence to collect the data/information. Then, analyze that data to reveal new insights to whatever question/s you first set. Before, eventually, updating your strategy to account for your new insights.

4 The pacing trap

Confusion or disagreement on when to move quickly and when to slow down.

Look out for the pacing trap when some people are reluctant to move ahead, whilst others aren’t. This reluctance will appear as curiosity or frustration. For example, a team member starts inquisitively asking more and more questions to understand what might happen. Meanwhile, other team members are rushing to close the conversation. This is a signal that you weigh the severity of your current decision-making differently. The individual member thinks the stakes are high, so is trying to control outcomes to minimize downside. Conversely, the team thinks the stakes are low, so are trying to get on with the job.

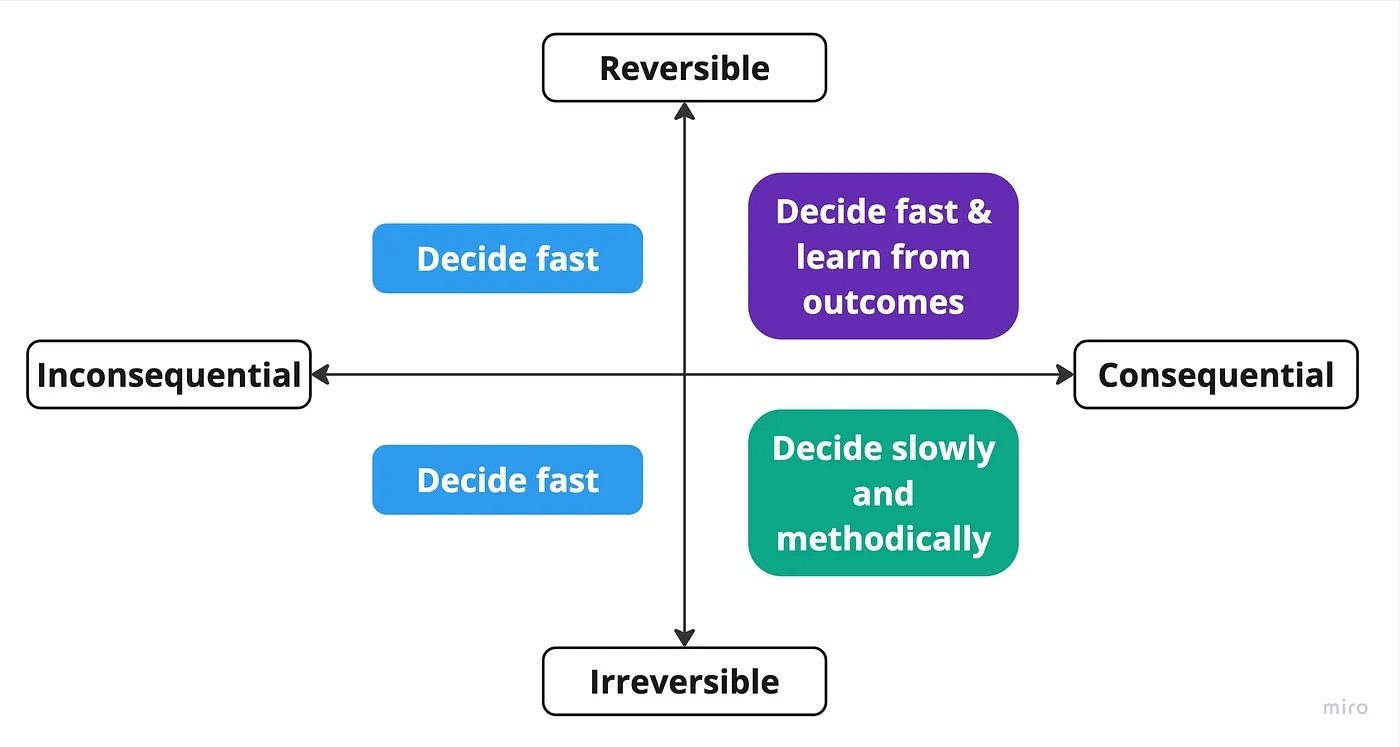

What to do: Determine whether the decision to be made is a two-way or one-way door. Developed by Jeff Bezos, the two-way door matrix helps you balance the impact of the decision to be made with the reversibility of the decision.

If the decision is reversible and inconsequential, decide fast. On the other hand, if the decision is irreversible and consequential, carefully deliberate and consult the data.